A Morning with Paik in Changsin-Dong

One morning in Seoul last May, I walked up the narrow backstreets of Changsin-dong to find the Nam June Paik Memorial House. Nestled into the hillside, it’s a modest hanok—restored from a 1960s wooden home and quietly unassuming. It stands on the site where Paik spent part of his childhood. And while little of that life remains, something in the atmosphere still hums.

Inside, the permanent exhibition Tomorrow, the World Will Be Beautiful unfolds slowly, almost like a musical score. There’s no strict chronology—just moments. You enter through Gate―Gate―Gate, a glowing monitor-arch that plays loops from Good Morning, Mr. Orwell and footage of Paik’s return to Korea. It feels more like tuning into a broadcast than stepping into a museum.

Other pieces surface as fragments of memory and play. Water―Moon recreates the light Paik once watched reflect off a water basin as a child. TV Mirror – Self-Portrait stares back at you from the wall—part shrine, part joke. Piano Table sits in the café, reassembled from smashed parts, a nod to Paik’s irreverent collisions of form, music and destruction.

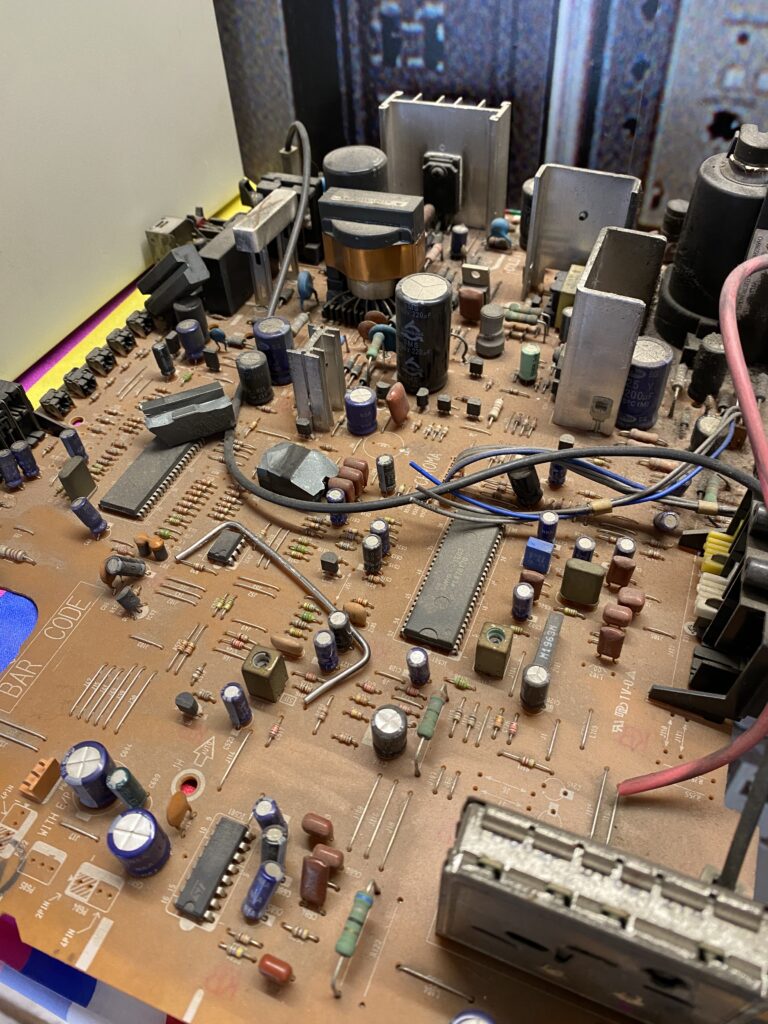

In the smallest room, Finding Nam June Paik Archive gathers replicas of objects from his life—books, toys, broken machines—assembled through acts of reconstruction and imagination. The result isn’t a historical record so much as a poetic one: an archive made not only of objects, but of memories.

Even the use of interactive technology was carefully integrated into the exhibition. As part of Nam June Paik’s Story – Tomorrow, the World Will Be Beautiful, an iPad app—developed for international and younger visitors—offered a playful, nonlinear path through Paik’s world. Through stories, visuals, and layered prompts like Learn, Activity, and Imagine, the app didn’t guide you toward a fixed biography. Instead, it echoed Paik’s approach: curious, non-hierarchical, and always in motion.

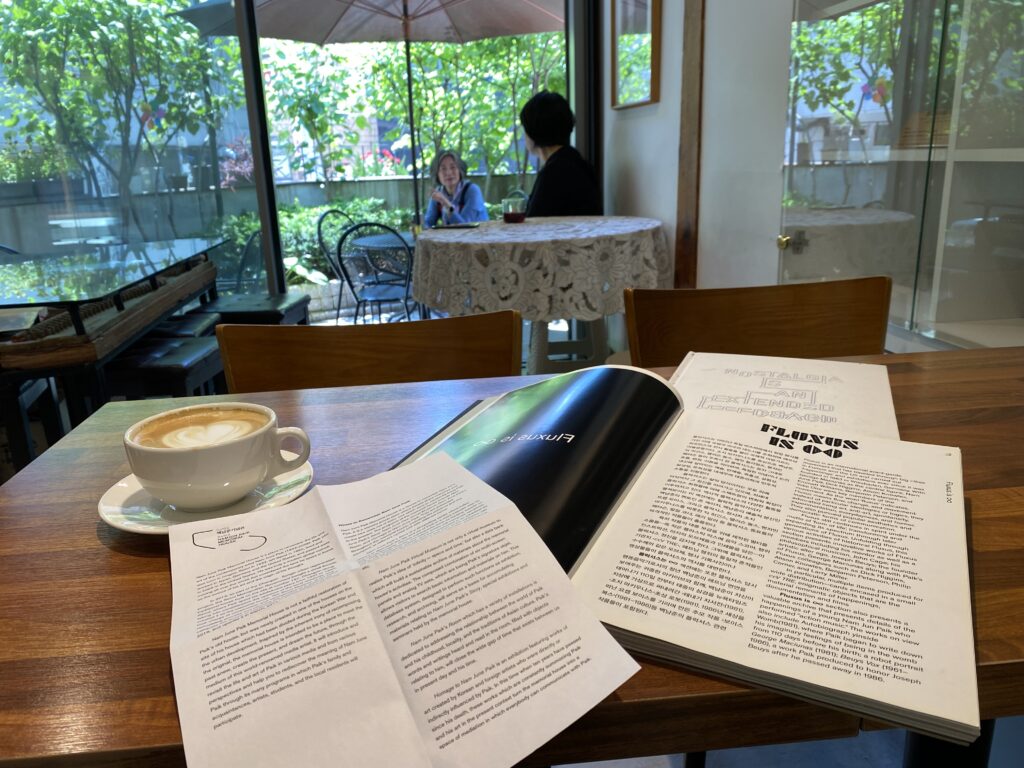

After spending time in the exhibition, I wandered into the small café tucked inside the house, run by local residents from the Changsin-dong neighborhood. Two older women were sitting on the terrace, chatting and smoking. I told the woman behind the counter—through simple words and gestures—about our project and how Paik continues to shape the way we think. She smiled, made me a cappuccino, and I sat down beside the piano with a book, letting the morning unfold in its own quiet rhythm.

I left the Memorial House with no firm conclusions—just a sense of resonance. The visit didn’t clarify who Nam June Paik was. Instead, it offered a method: poetic, relational, fragmentary. In this house, that doesn’t feel like a promise. It feels like a broadcast Paik left running, waiting for us to tune in.